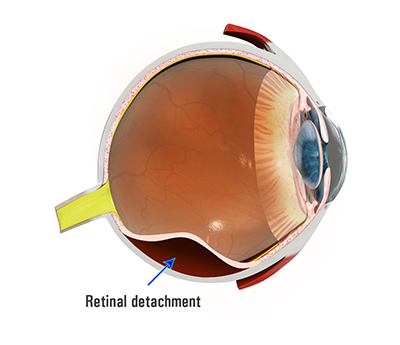

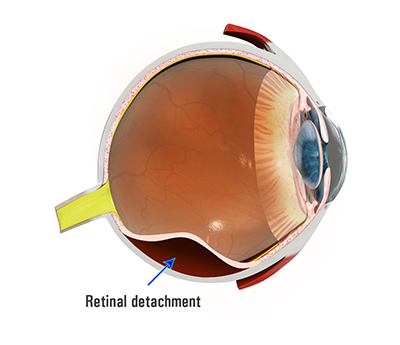

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment occurs when the retina is separated from the underlying eye wall tissues and loses its function. This usually starts in the periphery of the retina and progresses towards the centre. The retina loses function when it is detached because nutrients cannot reach the retina. The patient notices blurred vision or a curtain coming across the vision. A retinal detachment is a serious condition and may result in permanent loss of vision or even blindness unless treated promptly. In Australia 1 in 10,000 persons per year will develop a retinal detachment.

In order to understand retinal detachment and its treatment, it is helpful to know a little about the eye and how it works.

The eye can be compared to a camera. The pupil of the eye is like the aperture of a camera, regulating the amount of light entering the eye. Light is focussed by the cornea, the clear window into the eye, and the lens, which lies behind the pupil.

The retina is the light-sensitive nerve tissue that lines the inner wall of the eye, like the film in a camera. Rays of light enter the eye, passing through the cornea, pupil and lens before focusing on to the retina. The retina contains photoreceptors which convert light into electrical impulses. In the healthy eye these impulses are sent via the optic nerve to the brain, where sight is interpreted as clear, bright, colourful images.

The retina lies on a layer of supporting tissue known as the retinal pigment epithelium or RPE. The RPE is important as it nourishes the photoreceptors and removes their waste products.

The macula is a small area at the centre of the retina. It is very important as it is responsible for our central vision. It allows us to see fine detail for activities such as reading, recognising faces, watching television and driving. It also enables us to see colour.

The vitreous is a clear, jelly-like substance which occupies about two thirds of the volume of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous develops structural changes and may pull away from its attachment at the back of the eye. This is termed a posterior vitreous detachment or PVD . Usually a vitreous detachment does not cause significant problems.

Anyone can develop a retinal detachment at any time, however some people are more at risk of the condition:

Predisposing factors for retinal detachment include:

- Age: posterior vitreous detachment occurs more commonly as we age and it is at the time of PVD that there is the greatest risk of retinal detachment.

- Myopia: short-sightedness increases the risk of retinal detachment up to 10-fold, because a myopic eye is larger than average and the retina is thinner and weaker and more prone to develop a tear during PVD. Myopes also develop PVD at a younger age.

- Family history of retinal detachment

- Cataract surgery: previous intraocular surgery will slightly increase the risk.

- Trauma: previous injury to the eye or face increases the risk.

- Weak areas in the retina (lattice degeneration).

If you have developed a retinal detachment in one eye, your fellow eye may be at risk. If weak areas of the retina or retinal tears are discovered in the fellow eye then preventive laser treatment may be necessary to reduce the risk to the fellow eye.

Sometimes a retinal detachment is discovered during a routine examination by your optometrist or ophthalmologist. However, most patients develop a change in vision.

Common symptoms of posterior vitreous detachment include:

- Flashes of light: bright and rapid flashes, caused by the vitreous gel pulling on the retina.

- New floaters or a sudden increase in floaters. These may be tiny dots or larger clouds or cobwebs which move across the vision.

Common symptoms of retinal detachment include:

- A dark shadow or curtain starting at the edge of the field of vision and moving centrally.

- Blurred or distorted central vision if the macula becomes detached.

These symptoms do not always mean a retinal detachment is present. However, you should see your ophthalmologist as soon as possible.

Patients with retinal detachment require surgery to put the retina back into its proper position. An acute retinal detachment is a medical emergency. There is a limited window of time in which to repair the detachment before permanent loss of vision occurs. The aim is to perform surgery before the retinal detachment progresses to involve the central macula. If the macula is detached at the time of surgery then the central vision may never fully recover.

There are several different ways to repair a retinal detachment. The decision on which type of surgery is appropriate for you depends on the characteristics of your detachment. The principal of surgical repair is to reattach the retina to the eye wall by draining the fluid from under the retina, and using laser surgery or cryotherapy to seal the tear.

The two major types of surgical repair for a detached retina are vitrectomy and scleral buckle. In complex retinal detachment cases both approaches may be necessary for a successful result.

The retinal detachment is repaired from the inside. Tiny microsurgical instruments are placed inside the eye. The vitreous gel, which is pulling on the retina, is removed from the eye using a vitreous cutter and usually replaced with a gas bubble. In cases of advanced retinal detachment, where long term pressure on the retina is required, silicone oil or heavy liquid may be used. Your body’s own fluids will gradually replace the gas bubble.

The retinal detachment is repaired from the outside. A thin silicone band (scleral buckle) is sutured in place around the outer circumference of the eye beneath the muscles that move the eye. This is invisible once the eye has healed, and works by counteracting the force pulling the retina out of place. The ophthalmologist drains the fluid under the detached retina from the eye, allowing the retina to settle back to its normal position against the wall of the eye. A temporary gas bubble may be injected into the vitreous space inside the eye to keep the retinal tear closed against the wall of the eye.

You can expect some discomfort after surgery. Your ophthalmologist will prescribe eye drops for you and advise you when to resume normal activity.

If a gas bubble was placed in your eye, you may be required to maintain a certain head position for several days in order for the gas to place pressure on the area of retinal detachment. This may continue for several days. The gas bubble will gradually disappear over days to weeks depending on the type of gas used. There is equipment available to hire to make this position more comfortable.

Do not fly in an airplane or travel to high altitudes until you are told the gas bubble is gone. A rapid increase in altitude may cause a dangerous rise in eye pressure.

You will be given a wrist bracelet to warn Medical Staff against giving nitrous oxide whilst gas remains in the eye.

If gas is used during surgery, vision will be poor until the gas bubble is absorbed by your body.

Untreated retinal detachment usually results in permanent, severe vision loss or blindness, and this should be borne in mind when considering whether you should undergo retinal detachment surgery.

Any surgical procedure carries risk. Using modern microsurgical techniques the risks of retinal detachment surgery are low, however occasional complications can occur.

Haemorrhage and infection in the eye are rare but potentially serious complications which may cause permanent loss of vision or even loss of the eye.

Most retinal detachment surgery is successful, however a second operation is sometimes required. This may be due to scarring of the retina called proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). This scar may pull on the retina causing it to tear and re-detach. If the retina cannot be reattached, the eye will continue to lose sight and ultimately becomes blind.

Anaesthetic complications may occur. General anaesthesia always carries a very small but potentially severe risk. These risks will be explained by the anaesthetist prior to surgery.

If you have any questions concerning the procedure or possible complications please do not hesitate to contact Dr Isaacs or the team at Perth Retina.